1730: The Beginnings of American Masonry

Like so many Masonic events, the first American appearance of Freemasonry is not precisely known. Jonathan Belcher (1681–1757), a native of Cambridge, Massachusetts and later Governor of the Colonies of Massachusetts and New Hampshire from 1730–41 and the Colony of New Jersey from 1747–57, was made a Mason in London ca. 1704.

It is possible he held private Lodges at his residence before time-immemorial or chartered Lodges appeared. On 5 June 1730, the premier Grand Lodge appointed Daniel Coxe (1673–1739) Provincial Grand Master for New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, giving the first official Masonic recognition of the English colonies. Bro. Coxe does not seem to have exercised his authority, even though he lived in New Jersey from 1731–1739.

The Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania possesses a book marked “Liber B” which contains the records of the earliest known Pennsylvania and American Lodge. The first record is for 24 June 1731, and in that month Benjamin Franklin (1705–1790) is entered as paying dues five months back. Franklin’s entry implies Lodge activity from at least December 1730 or January 1731.

Provincial Grand Masters were appointed after Daniel Coxe from 1733 through 1787: twenty-two by the moderns, six by the ancients, and four by Scotland.

In 1775 John Batt initiated fifteen free African-Americans in Boston. Batt was Sergeant in the 38th Regiment of Foot, British Army and Master of Lodge No. 441, Irish Constitution. When the Regiment and Lodge departed in 1776, the fifteen new Masons were left with a permit to meet, to walk on St. John’s Day, and to bury their dead. They in turn applied to the Grand Lodge of Moderns for a warrant and were chartered as African Lodge No. 459 on 29 September 1784 with Prince Hall as the first Master.

In 1792 when the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts was formed, African Lodge did not join but remained attached to England. This could be due to loyalty to the premier Grand Lodge or to racism from the newly formed Grand Lodge. However, the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts also didn’t recognize St. Andrews Lodge, which had a Scottish charter. There is evidence that white Masons visited African Lodge and that England relied on Prince Hall for information on Boston Lodges. In any event African Lodge continued its separate existence until 1813 when it and all other English-chartered American lodges were erased from the roles of the newly formed United Grand Lodge of England. Then in 1827 officers of African Lodge declared themselves independent and constituted themselves as a Grand Lodge. From these origins grew the large Masonic organization known today as “Prince Hall Masonry.”

Most American Lodges originated from one of the British Grand Lodges—England, Scotland, and Ireland, though Germany, France, and other Grand Lodges issued charters. Traveling British military Lodges spread Masonry through much of North America as they initiated civilians in the towns where they were stationed. Also imported from England was the rivalry between the Ancient and Modern Grand Lodges. Many states had competing Grand Lodges that eventually merged after the Union of 1813 in London, though South Carolina did not see Masonic unity until 1817. Modern Masons tended to be conservative in promoting the fraternity, prosperous, and loyalists, while Ancient Masons were aggressive in expanding Lodges, working-class, and revolutionaries.

The early forms of Masonic ritual in the United States are less known that those in England and France. We do not have the large number of 18th century documents—Gothic constitutions, manuscript catechisms, memory aides—that can be found in Europe. Presumably the first rituals were transmitted mouth-to-ear, and Lodges may have patterned their ceremonies after some of the exposés, either imported or printed domestically.

The first American exposé was Benjamin Franklin’s 1730 reprint of The Mystery of Freemasonry (intended as an attack upon rivals), but there do not seem to have been any exposés of American ritual practices until the anti-Masonic period, ca. 1826–1840.

The Influence of Itinerant Masonic Lecturers

With a diversity of ritual sources, the work in American Masonic Lodges must have been variegated during the 1700s. This began to change in 1797 when Thomas Smith Webb (1771–1819) published The Freemason’s Monitor or Illustrations of Masonry. It acknowledged that “The observations upon the first three degrees are many of them taken from Preston’s ‘Illustrations of Masonry,’ with some necessary alterations” to make them “agreeable to the mode of working in America.”

Webb was the first and most prominent of several Masonic Lecturers who toured the country teaching a uniform of ritual to Lodges, Chapters, and any other body they could convince to pay their fees. These lecturers often had “side degrees” available for sale or as gifts. Webb trained Jeremy Ladd Cross (1783–1861) who succeeded Webb as the generally recognized chief ritualist. Cross’s great contribution was his 1819 The True Masonic Chart or Hieroglyphic Monitor. It was largely Webb’s Monitor with a few small textual changes and one major visual addition: forty-two pages of engravings by Bro. Amos Doolittle.

Doolittle’s engravings did more than illustrate Cross’s text, they provided a memory map for students learning the ritual. Each image on a page was a milestone in the lectures. By associating an image with a portion of ritual, it was possible to mentally review an entire lecture by thumbing through a few pages of Cross’s Chart. The book was very successful and has influenced the artwork in almost every subsequent American Masonic monitor.

Other Masonic lecturers trained by or with Webb and Cross include John Barney (1780–1847), James Cushman (1776–1829), David Vinton (d. 1833), and John Snow (1780–1852). They each seemed to concentrate on a different part of the country, much as salesmen have defined territories. There was some cooperation among the lecturers and not a small amount of competition.

The Royal Arch

The first “high degree” to appear in America was the Royal Arch Degree. In fact, the first recorded conferral of this degree anywhere occurred in December 1753 at Fredericksburg Lodge in Virginia, where George Washington (1731–1799) was initiated an Entered Apprentice in 1752. The American Royal Arch ritual is based upon the story of Jeshua, Zerrubabel, and Haggai and the rebuilding of the second Temple in Jerusalem. The degree began to spread steadily throughout the colonies:

1758—organization of Jerusalem Chapter in Philadelphia;

1769—organization of St. Andrew’s Chapter, Boston;

1790—organization of Cyrus Chapter Newburyport, Massachusetts;

1792—organization of a Chapter in Charleston, South Carolina;

1794—organization of Harmony Chapter, Philadelphia.

Other unrecorded or forgotten degrees and chapters doubtlessly occurred. In 1795 the First Grand Chapter was formed in Pennsylvania, and in 1797 the first national American organization was created—the General Grand Chapter of the New England States, which is today the General Grand Chapter of the United States. Additional Grand Chapters quickly followed in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and Rhode Island in 1798. By 1830 there were twenty-one Grand Chapters in the United States.

The early conferral of the Royal Arch Degree seemed to be based on the authority inherent in the charter of a Lodge. Not surprisingly, it was Ancient Lodges that were most likely to see this high degree authority inherent in their charters. Royal Arch Chapter in the United States, in contrast to their English counterparts, quickly organized themselves into state Grand Chapters and, with the exception of Pennsylvania and Virginia, quickly placed themselves under the authority of the General Grand Chapter.

A quirk of American Royal Arch Masonry is worth noting: (unlike elsewhere) the American presiding officer is not the King, representing Zerrubabel, but the High Priest, representing Jeshua.

The Growth of the Chapter Degrees

As Lodges had a “chair degree,” the Past Master’s Degree, it only made sense that the Royal Arch should have one too, and so the Order of High Priesthood came into being. It is not mentioned in Webb’s 1796 Monitor, but it is in his 1802 edition as well as Cross’s 1819 Chart. It is usually conferred on High Priests before they can assume the Oriental Chair of Solomon. The degree, still worked today, may have had European ancestors, but its genealogy is uncertain.

As in England the Royal Arch Degree in the United States can only be conferred on Past Masters. American practice soon required the conferral of the chair ceremony to qualify candidates as “virtual Past Masters.” The Chapter degree seems to have contained the essential elements of the Lodge degree, but the candidate was given humorous trials and tribulations to endure.

The Growth of the Chapter Degrees

The earliest record of the Mark Degree is in 1783 at the Royal Arch Chapter in Middleton, Connecticut. Soon the Mark was adopted by Royal Arch Chapters as the first in their sequence of degrees. This is in contract to most European jurisdictions where the Mark is independent and controlled by its own Grand Lodge.

The Most Excellent Master Degree, a uniquely American degree in origin, first appeared by name at the Middleton Chapter with the Mark Degree in 1783. Its legend revolves around the completion of the Temple of Solomon and the placement of the keystone in the Royal Arch. It may contain elements from older European degrees, but its current organization is unique to the United States. Thomas Smith Webb published a description of this degree in his 1797 monitor as the third of three degrees leading to the Royal Arch, and it has remained in that position until today.

The sequence of degrees conferred in American Royal Arch Chapters since then (except for Virginia and West Virginia) is

1. Mark Master Mason,

2. Past Master,

3. Most Excellent Master,

4. Royal Arch Mason,

5. Order of High Priesthood for High Priests.

The Cryptic Degrees

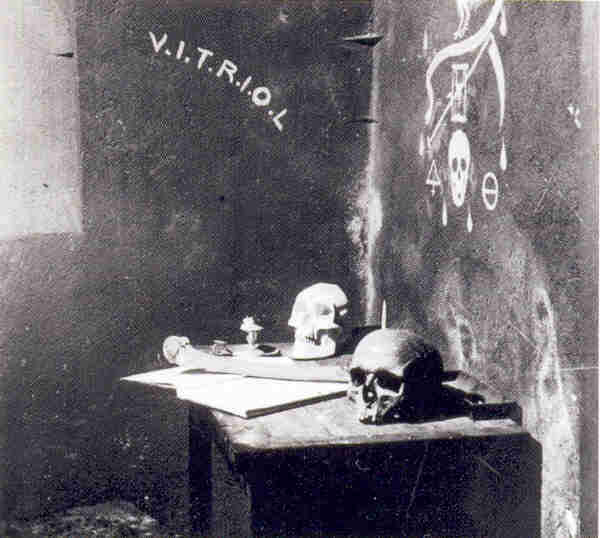

The Degrees of Royal and Select Master seem to have originated as side degrees available from itinerant Masonic lecturers. They are known collectively as the “Cryptic Degrees” or the “Cryptic Rite” because their legend deals with the secret vault or crypt beneath King Solomon’s Temple.

Cross included these two degrees in his popular 1819 illustrated monitor, producing a nine-degree system extending from Entered Apprentice to Select Master. The degrees were some times conferred in Royal Arch Chapters, but slowly emerged as independent Masonic bodies, governed by state Grand Councils of Royal and Select Masters and a national General Grand Council. The earliest independent Councils were formed in

1810—New York City,

1815—New Hampshire,

1817—Massachusetts, Virginia, and Vermont,

1818—Rhode Island and Connecticut.

By 1830 there were Grand Councils in ten states. Under the influence of Cross’s Chart and other monitors, the Select Master’s Degree came to be viewed at the culmination of “Ancient Craft Masonry,” even if Councils were found in only a few metropolitan areas and their degrees available to only a few. This is probably the beginning of the American “York Rite,” consisting of the Chapter of Royal Arch Masons, Council of Royal and Select Masters, and Commandery of Knights Templar.

Knights Templars and the American York Rite

The first reference to a Masonic Templar degree is found in the minutes of St. Andrews Lodge, Boston, an Ancient Lodge, when on 9 April 1769, William Davis received the Excellent, Super Excellent, Royal Arch, and Knight Templar Degrees. In 1796 the first Commandery (or Encampment or Priory) was established in Colchester, Connecticut, and eventually received a charter from England in 1803.

Today in America a Commandery of Knights Templar confers the Order of the Red Cross, the Order of Malta, and the Order of the Temple on Christian Masons. In 1816 the Order of Malta was placed as the last degree in the series until 1916 when it returned to second place.

The Red Cross legend is similar to the Knight of the East and Prince of Jerusalem detailing the return of Zerubbabel from Babylon to Jerusalem to rebuild the Temple. It is entirely out of place among Christian chivalric orders. Nonetheless it remains and provides an important part of the York Rite legends.

Taken together, the Craft Lodge, Royal Arch Chapter, Royal and Select Council, and Knights Templar Commandery form the American “York Rite.” The name is inexact as the degrees did not originate in York, England, but then again the Scottish Rite did not originate in Scotland.

Reflecting the widespread belief that the York Rite was the purest and oldest form of Masonry, some American Grand Lodges originally styled themselves, “Ancient York Masons” (A.Y.M.)

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite

A high degree event in the United States occurred on 31 May 1801 when John Mitchell (ca. 1741–1816) elevated Frederick Dalcho (1770–1835) to the 33rd Degree, and they then elevated another seven until there was a constitutional number to open a Supreme Council. Their actions were announced to the world in a circular dated 4 December 1802. The opening of the first Supreme Council 33° was preceded by considerable “Scottish” activity.

Etienne Morin (1693?–1771) received authority in 1761 from Paris or Bordeaux to promote Masonry throughout the world. This included propagating a rite of twenty-five degrees, sometimes known as the Rite of Perfection. Morin moved to San Domingo and soon appointed six Inspectors General. The most successful of these was Henry Andrew Francken (d. 1795), from whom fifty-two Inspectors descended, though he only appointed six.

After Morin’s arrival in America, bodies of his rite were soon established:

1764—Loge de Parfaits de Écosse, New Orleans, Louisiana;

1767—The Ineffable Lodge of Perfection, Albany, New York;

1781—Lodge of Perfection, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania;

1783—Lodge of Perfection, Charleston, South Carolina;

1788—Grand Council, Princes of Jerusalem, Charleston, South Carolina;

1791—King Solomon’s Lodge of Perfection, Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts;

1792—Lodge of Perfection, Baltimore, Maryland;

1797—Sublime Grand Council, Princes of the Royal Secret, Charleston, South Carolina;

1797—La Triple Union, Chapter of Rose Croix, New York. (17)

Inspectors propagated the degrees of this rite with little organization, often for the fees they could negotiate. The Supreme Council’s motto, Ordo ab Chao, is indeed appropriate for the situation.

Webb’s Monitor had monitorial instructions for the ineffable degrees, which served to make American Masons aware there was more than the York Rite. Thus when the Mother Supreme Council formed itself in 1801, it did not operate in a vacuum.

In August 1806 Antoine Bideaud, a member of the Supreme Council of the “French West India Islands,” visited new York City and found an opportunity to make a little extra money.

He conferred the Scottish Rite degrees on four Masons for $46 each and then created a “Sublime Grand Consistory, 30°, 31°, and 32°.” Bideaud’s authority was for the islands only and certainly did not extend into New York, which was under the jurisdiction of the Charleston Supreme Council. (18)

In New York City in October 1807, Joseph Cerneau (d. 1827?), a jeweler from Cuba, constituted a “Sovereign Grand Consistory of Sublime Princes of the Royal Secret.” Cerneau was a “Deputy Grand Inspector, for the Northern part of the Island of Cuba” under Morin’s rite. His patent limited him to confer the 4° through 24° on Lodge officers, and the 25° once a year. Early records are sufficiently vague that it cannot be determined if the original members of Cerneau’s Consistory thought they had the 25° or the 32°. With even less authority than Bideaud, Cerneau launched his foray into high degree Masonry in New York.

The Bideaud organization was “healed” by Emmanuel de la Motta, Grand Treasurer of the Mother Supreme Council on 24 December 1813. This group assumed control of what is today known as the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction.

The Cerneau Consistory ignored de la Motta’s actions, but decided they had to expand their degrees to thirty-three to “keep up with the competition.” They eventually claimed jurisdiction over the “United States, Their Territories, and Dependencies.” Thus in 1830 there were three competing Supreme Councils in the United States. All three became dormant during the anti-Masonic period.

Side Degrees

The last category of pre-1830 degrees is “side degrees,” conferred under irregular circumstances with little formal authority. They sometimes were communicated by itinerant lecturers, sometimes by Masons who possessed the degree, sometimes for a fee, sometimes for free.

Some of these degrees could have coalesced into a rite if anti-Masonry hadn’t crushed them. There is scant information on them, sometimes little more than a title mentioned in passing. A search of all American Lodge minutes before 1830 might yield a few more names, but probably no more rituals.

Some of our information comes from two exposés from the anti-Masonic period, David Barnard’s 1829 Light on Masonry and Avery Allyn’s 1831 A Ritual of Freemasonry. Both authors seemed to been originally motivated in “saving” the American public by exposing the “evils” of Freemasonry. However, general interest in Masonry was spurred on by the public conferral of the degrees by anti-Masonic troupes.

This interest, in turn increased demand for exposés, especially those complete with passwords and grips. Bernard obliged this demand by adding the secret work from Delaunaye’s Thuileur, without regard for whether it matched the American degrees he described. It is often difficult to know if the degrees described were widely worked, if at all. Of these many degrees, only the Heroines of Jericho seems to be an American original. It survived and is worked today by Prince Hall Masons.

Another source of pre-1830 side degrees is a series of newspaper articles, “Recollections of a Masonic Veteran,” by Robert Benjamin Folger (1803–1892). Published in 1873–74, these articles describe his fifty years in Masonry with a few comments about side degrees. Finally, there is tantalizing evidence that Zorobabel Lodge No. 498 in New York City worked the Rectified Scottish Rite and may have conferred the fourth degree, Scottish Master.

Pre-1830 American Masonic Side Degrees:

Knight of the Christian Mark Bernard, Allyn

Knight of the Holy Sepulchre Bernard, Allyn

Holy and Thrice Illustrious order of the Cross Bernard, Allyn

Knight of the Three Kings, Allyn

Knight of Constantinople Allyn, Folger

Secret Monitor Allyn, Folger

Ark and Dove (RAMs only), Allyn

Mediterranean Pass Folger

Knight of the Round Table (fun degree), Folger

Aaron’s Band (similar to High Priesthood), Folger

Master Mason’s Daughter (for women), Folger

True Kindred (for women), Folger

Heroine of Jericho (RAMs, wives and widows), Allyn

1830: The End of the First Era of American Masonry

As early as March 1826 a New York Mason named William Morgan began plans to publish the “secrets of Freemasonry.” This created quite a stir in his small town of Batavia, New York. Neither Morgan, nor his potential readers, nor the local Lodge seemed aware that ritual exposés had been available in the United States since at least 1730 when Benjamin Franklin republished The Mystery of Freemasonry. Masons tried to purchase the manuscript from Morgan’s publisher, David Miller, a former Entered Apprentice Mason. When this failed, Miller’s printing company was set on fire twice, presumably by Masons.

Morgan, a ne’er-do-well in frequent debt, was jailed in Canandaigua, New York, for a debt of $2.00 assigned to Nicholas G. Chesbro, Master of the Lodge at Canandaigua. On the next day, 12 September 1826, Chesbro appeared at the jail with several other Masons and discharged his claim against Morgan. They escorted Morgan outside and into a waiting carriage. Before entering the carriage, Morgan was heard crying during a scuffle, “Help! Murder!” He was driven north to Niagara County and held in the old Powder Magazine at Ft. Niagara until 19 September. Morgan was never seen thereafter.

Morgan’s abduction, disappearance, and presumed murder set off a social and political crisis in the United States. Many came to believe that Freemasonry was a secretive power behind the government, murdering those who dared cross it. Soon the fear of Masonry manifested itself in the creation of the first major “third part” in American politics: the Anti-Masonic Party. The party attracted reformers, abolitionists, and idealists, but its primary purpose was the destruction of Freemasonry and other “secret societies.” From about 1826 to 1840 the anti-Masonic movement swept across the country. The northeastern states, where the Craft was most prosperous, endured the worst destruction, but few parts of the country was spared. By the time the Anti-Masonic Party collapsed as a political force in 1840, Freemasonry began to reemerge, but as a more conservative organization.