In 1925, Rudyard Kipling wrote in the London Times, "I was Secretary for some years of Hope and Perseverance Lodge No. 782, E.C. Lahore which included Brethren of at least four creeds.'

"I was entered by a member of Bramo Somaj, a Hindu; passed by a Mohammedan, and raised by an Englishman. Our Tyler was an Indian Jew.'

"We met, of course, on the level, and the only difference anyone would notice was that at our banquets, some of the Brethren, who were debarred by caste from eating food not ceremonially prepared, sat over empty plates."

The Lodge minutes prove the details of his Entry to be wrong and that Kipling was in fact entered, passed and raised by Englishmen.

What is more interesting however is that Kipling, despite writing much that many now consider deeply racist and hateful toward non white, Christian Englishmen, would feel compelled to create a false story.

Kipling obviously wanted to illustrate a cosmopolitan brotherhood, albeit one that existed within a distinctly English institution strictly administered along the same racial and class hierarchical arrangements that existed in every other aspect of British colonial life.

This phenomenon is examined in the book "Builders of Empire" (interview podcast with the author, book abstract and several reviews to follow):

Author of “Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927”. In the interview Ms. Harland-Jacobs is taken off track from her main thesis and even bloodied a bit. Unfortunately the interview barely addresses her thesis but it is posted here.

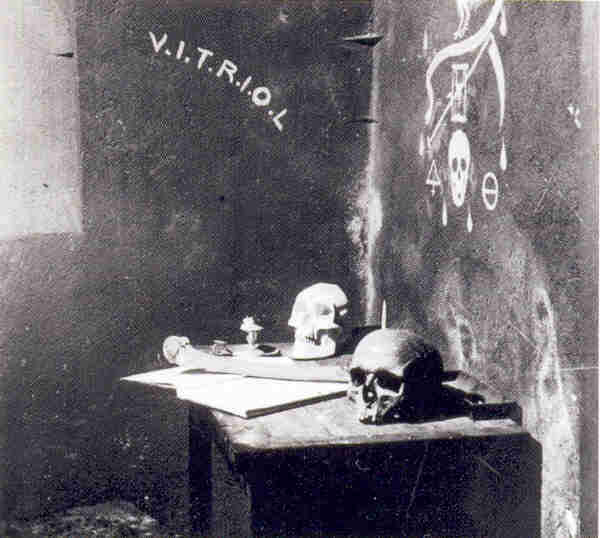

Abstract: Emerging in Britain during the seventeenth century, the Masonic brotherhood—which claimed to admit any free man, regardless of his religion, social status, political orientation, and race (provided he believed in the existence of a supreme being)—taught its members lessons of self-improvement, spirituality, and benevolence. During the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the fraternity suited itself remarkably well to the British Empire.

It spread primarily through the activities of lodges in British Army regiments, which resulted in the development of a vast service network that was fundamentally global and masculine in nature. Looking at the British North Atlantic world between 1751 and 1918, this dissertation explores the reciprocal relationship between Freemasonry and imperialism. It asks how Freemasonry contributed to the building and consolidation of the British Empire and what the fraternity reflected about the broader imperial context.

Having conducted research in Masonic and public archives on both sides of the Atlantic, I draw on a wide range of manuscript and published sources, including correspondence; private papers of prominent Freemasons; British government documents; proceedings of the English, Irish, Scottish, and Canadian grand lodges; and Masonic speeches, sermons, periodicals, pamphlets, and monographs.

I deploy the methodology of world networks history to argue that cultural institutions played a critical role in British imperialism and that the imperial and metropolitan spheres were highly interconnected arenas. As it underwent the simultaneous processes of bureaucratization in the metropole and global expansion, Freemasonry experienced a transformation. Despite its consistent cosmopolitan claims, it became increasingly Protestant, middle-class, loyalist, and white over time. From the mid-nineteenth century on, Freemasonry marched hand in hand with the British imperial state. Its network connected the metropolitan and colonial spheres, fostering what I describe as an imperialist identity among its members and becoming implicated in the increasingly racialized imperialism of the late nineteenth century.

Like cosmopolitanism, imperialist identity is an example of an under-studied supra-national identity. Appreciating its role in imperialism is crucial for understanding the timing and location of national identity formation and the hegemonic function of cultural institutions in the imperial arena.

The Lodge Room's Review:

“Builders of Empire: Freemasonry and British Imperialism, 1717-1927″ by Jessica L Harland-Jacobs (Univ of N Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2007)

Modern, post-Enlightenment thinking tends to characterize, in hindsight, an intellectual movement that became a veneer of noble sentiment for the prevalent power arrangements, abuses and injustice. Post-Enlightenment modernists over the better part of the century have pointed to ample evidence for this view. Imperialism, colonialism, neo-colonialism, slavery, genocide, racial and ethnic disparity and economic, political and social injustices seem to coincide with the rise and decline of the Enlightenment. Barely a single institution of major significance has been unexamined for its role in that problematic era.

There is one major institution that has escaped serious examination: Freemasonry. Historian Jessica Harland-Jacobs has undertook to right this omission. Her “Builders of Empire: Freemasonry and British Imperialism, 1717-1927″ examines particularly the role of Freemasonry through the rise and height of British imperialism. The results are hardly surprising.

From a pre-Enlightenment, Christian brotherhood with the presence of some random moral speculators, British Freemasonry quickly transformed to imperialist state machinery. If there is anything surprising perhaps even to the well informed student of the period, it is the major role of Freemasonry in reinforcing the imperialistic social order.

There may be an aspect of "blaming the plate for the meal" in Ms. Harland-Jacobs' book. Institutions evolve with society, their framework being used for whatever the energies and the imagination of the time order. Freemasonry can be no more (or less) condemned for its role as the church or educators in British public schools. These institutions however have examined themselves, as they are still crucial to modern society whereas Freemasonry is not. A book like this does a great deal of good for all concerned to understand the era of British imperialism and its underpinnings. It does even more for our understanding the continuing evolution of Freemasonry.

A final note. It is lamentable that a Freemason did not write such an excellent and needed work in this field. Such authorship could have been an indication that Freemasonry is moving into a new period of intellectual and societal relevance. The popularity of Ms. Harland-Jacobs' book in the Masonic community nevertheless may be reason to take heart.

------------------------------------------

Editor, Pietre Stones Review of Freemasonry. Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927 (review)

Although white Protestant men of the upper classes vastly predominated with Freemasonry much less established abroad, eighteenth century British Masonry did have room in its some of its lodges for Jews and Muslims, African Americans, South Asians and others. Freemasonry's cosmopolitanism was by definition fraternal. Eighteenth-century Masonry also included men of a diverse range of political opinions who both supported and challenged the imperialistic Whig oligarchy running Hanoverian Britain and its growing empire.

The acceptance of the "natives" neo-colonial functionaries in the lodges where they were told they were brothers and equals assisted in psychologically co-opting that class. Despite the real inequality in the Freemasonry of the day, membership provided a reward and a re-enforcing concept for the whole practice of neo-colonialism itself. Masonry thus reflected and contributed to the "fundamental reordering of the Empire" as the old Atlantic empire transformed into the so-called "Second British Empire" of the nineteenth century.

It is not surprising then that so many leaders of liberation movements in the Third World spent time in lodges where the discerning eye might realize in a scaled version of the world of British imperialism. This could have only illustrated the differences between stated values and practice among the British.

Note: Specifically in some of her scholarship on pre-1717 Freemasonry (which has some bearing even for a book covering post 1717), Harland-Jacobs has not moved research forward and may have done inadequate study in keeping with this exhaustively well researched area.

She fails to understand or explain the complex rivalry with the increasingly egalitarian London based "Moderns" and the at least one faction of conservatively Christian "Antients" who many understand as largely Anglo-Irish and to some degree Scotch-Irish, as well as the alleged Jacobite element in some Scottish and some Anglo-Irish lodges.

These issues are complex and cloudy and thus might have been best avoided by dealing with British imperialism outside of the British isles. It is Masonry's influence in the overseas empire in fact where her work is unrivaled in its research and informative in its interpretations.

Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927 (review)

If you want to understand — if you think you can bear to understand — the hypocrisy of liberal, Anglo-American imperialism, I think there is no better way of doing it than studying the history of Freemasonry, (and to a slightly lesser extent, the history of post-1688 ‘Glorious Revolution’ Anglicanism).

Freemasonry, in its Anglo-American form, is the absolute quintessential representation of liberal hypocrisy, in every single respect: religiously, racially, sexually, geopolitically, culturally, and intellectually. Its ability to deploy terms like “Freedom”, “Justice” and “Equality” quite unblushingly to mean whatever it wants them to mean is absolutely unrivalled. “Builders of Empire: Freemasonry and British Imperialism, 1717-1927″ by Jessica L Harland-Jacobs (Univ of N Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2007) makes this absolutely clear.

There are loose ends and errors in tangential subjects that may irk anyone familiar with early Freemasonry and politics in Britain: she does not in give enough attention to the other streams of Freemasonry, those not in accordance with the criteria of the Grand Lodge of England, French Freemasonry in particular.

She minimises the extent to which non-English Freemasonry went its own, rather less hypocritical and more interesting way. She makes it clear that in practical terms North American Freemasonry has managed to be very closely allied with the English, in a sort of woolly ‘fraternal’ way.

It has never, to put it the other way, been actually hostile to English Freemasonry. North American Freemasonry has been distinctly hostile to French and other continental European Freemasonries, and the various extra-European Freemasonries allied to them, have not accepted Anglo-American presumptions. To quote an interesting but regrettably brief passage from the book:

“Latin Masonry” was the term twentieth-century British Masons used to describe European Grand Lodges and their offshoots with which the English Grand Lodges had broken off communications in the late 1870s.

The original cause of the rift was the decision on the part of the Grand Orient of France to admit atheists into the brotherhood in 1878. British Masons and their allies throughout the world had therefore refused to take part in various internationalist movements undertaken by the representatives of “Latin Masonry” in the 1890s and early 1900s.

In 1919 the European Masons proposed the formation of a Masonic International Association. At the first congress, held in October 1921, representatives from most European grand lodges, as well as the Grand Lodge of New York and the Grand Orient of Turkey, met to discuss their common aims. The grand lodges of Britain, the empire, and the United States (except New York) refused to send representatives to the congress.

It is not altogether clear whether this dispute was ever really resolved, see here. An amusing footnote from the same book:

Recently returned from Africa in 1922 General Sir Reginald Wingate (governor general of the Sudan between 1899 and 1916, High Commissioner for Egypt from 1917 to 1919, District Grand Master of Egypt and Sudan from 1901 to 1920) noted the existence of many lodges that worked in Arabic and “various European languages.” Describing some of these lodges as “centres of sedition and even of revolution,” he happily reported that “British Freemasonry is entirely free of any such taint.” (Our emphasis.)

Wednesday, March 3rd, 2010